So I was thinking a bit about frequent releases. There are many agile books and articles that explain how more frequent releases are a good thing. However, to many people in management, this is counter-intuitive. They say "Slow means safe. Slowing down means more time to improve quality, more time to test, and more time to fix bugs. Also slow is cheaper, because it's less overhead costs." I've seen a lot of projects where release frequency slows down, especially after the initial development burst and launch of a product, and I think this is a shame.

So how do I go about explaining people that the slow-means-safe line of thought is wrong?

I've come up with a little model I'd like to go through here.

I start off with defining a Rate of Development, which we'll assume is constant throughout the model (leaving out factors as motivation and skill).

Now, having a high rate of development is not worth anything if we're not Doing the Right Thing. This symbolizes working in the right direction, and our Performance ultimately is decided by Doing the Right Thing at our Rate of Development. Performance represents the long term success of our organization.

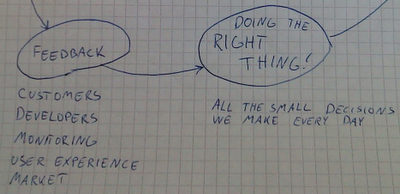

Now we won't pick at the RoD in this model (assumed to be constant), but rather look at DtRT: Doing the Right Thing encompasses all the hundred little decisions we make every day, from whether or not we should rename this method, which OS we choose on our servers, to which feature we choose to develop. So what tells us what is the right thing to do? Answer: Feedback.

Feedback comes from customer (support, sales, social media), developers (retrospectives, standups), monitoring metrics and logs on the product, doing user experience testing, market response and stuff like that. This feedback gives us the intelligence we need to Do the Right Thing.

How can we increase Feedback? Answer: With more Frequent Releases. This is fairly intuitive, releasing more frequently will increase the mass of Feedback in most channels.

At this point traditional management will cross their arms and say hold on, it's not that easy: We can't risk releasing more often, it's too dangerous. So, let us consider Safety as a parameter for that.

Safety means no nasty bugs or deployment botches. The problem with management is that they mix up what is the cause of the effect here. They see Frequent Releases as a driver for Safety going down, while in reality it is on the other side the factors lie.

So let's dig a bit deeper and see what leads to Safety. Here are the typical factors:

So how do I go about explaining people that the slow-means-safe line of thought is wrong?

I've come up with a little model I'd like to go through here.

I start off with defining a Rate of Development, which we'll assume is constant throughout the model (leaving out factors as motivation and skill).

Now, having a high rate of development is not worth anything if we're not Doing the Right Thing. This symbolizes working in the right direction, and our Performance ultimately is decided by Doing the Right Thing at our Rate of Development. Performance represents the long term success of our organization.

So so far we've got RoD x DtRT => Performance

Now we won't pick at the RoD in this model (assumed to be constant), but rather look at DtRT: Doing the Right Thing encompasses all the hundred little decisions we make every day, from whether or not we should rename this method, which OS we choose on our servers, to which feature we choose to develop. So what tells us what is the right thing to do? Answer: Feedback.

Feedback => DtRT

Feedback comes from customer (support, sales, social media), developers (retrospectives, standups), monitoring metrics and logs on the product, doing user experience testing, market response and stuff like that. This feedback gives us the intelligence we need to Do the Right Thing.

How can we increase Feedback? Answer: With more Frequent Releases. This is fairly intuitive, releasing more frequently will increase the mass of Feedback in most channels.

Frequent Releases => Feedback

At this point traditional management will cross their arms and say hold on, it's not that easy: We can't risk releasing more often, it's too dangerous. So, let us consider Safety as a parameter for that.

Safety => Frequent Releases

Safety means no nasty bugs or deployment botches. The problem with management is that they mix up what is the cause of the effect here. They see Frequent Releases as a driver for Safety going down, while in reality it is on the other side the factors lie.

So let's dig a bit deeper and see what leads to Safety. Here are the typical factors:

- Tests (automated tests, unit-, integration-, as well as manual testing where necessary)

- Good Code (fewer unexpected side-effects from making changes)

- Small Feature Set

The first two there are fairly obvious. The last one is a pill management has a hard time swallowing:

Releasing a Smaller Feature Set means more safety, because there are fewer features to figure out, develop, and to test in parallel. Fewer moving parts that can malfunction, so to speak.

Now the model is complete. Have a look at the complete thing:

(You can also draw a line from Doing the Right Thing leading back up to the factors increasing Safety.)

Typical objections from management that object to this model (exercise for the reader: are these fallacies or not?):

- Doing the Right Thing is better decided by planning/strategy/architecture, than by Feedback.

- Safety increases linearly with QA: 10 times as many features is just as well tested by 10 times the QA.

- Good Code is irrelevant to Safety. (Refactoring is actually regarded as a minus to safety in some places).

While Frequent Releases are the result of Safety and the drivers behind it, traditional management unfortunately sees it as a lever they can turn down to increase safety.

So, I'm not sure if the model will be of any help to you. For me it's just a nice way to explain the benefits of frequent releases to non-developers.

Also releasing frequently minimizes the stress of deployment, because to be able to release (and deploy) often, you need good automation and a clean process, which is well understood by doing it on a regular basis instead of once a quarter or worse.

ReplyDelete@Patrick: Thanks for the comment! Good point. There could be another bubble above Safety called Process or Routines that apply to the stability of doing releases. Releasing frequently feeds directly back there, like you say.

ReplyDeleteGreat thoughts. Somewhat reminds me to the influence diagrams found at the end of Kent Beck's good old TDD book.

ReplyDeleteIt looked something like more frequent tests -> more _confidence_ -> productivity.

This looks the same, more fundamental principle ('test' generalised as 'feedback'). Apart from the link mentioned above (frequent releases forces you to automate things better, which in turn is a positive feedback loop on both frequent releases and performance directly), it seems to help eliminate the other hindrance against itself. That is, I found a common reason for not making a release is lack of confidence in stability/code maturity - which this loop helps with: frequent feedback -> confidence -> performance.

@Gin: Thanks for commenting! My thoughts are very influenced by Beck, so that figures :)

ReplyDelete